Section B: Bichirs in the aquarium

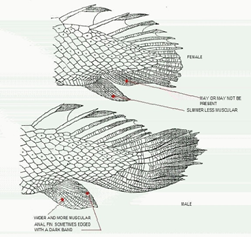

Bichirs as pets

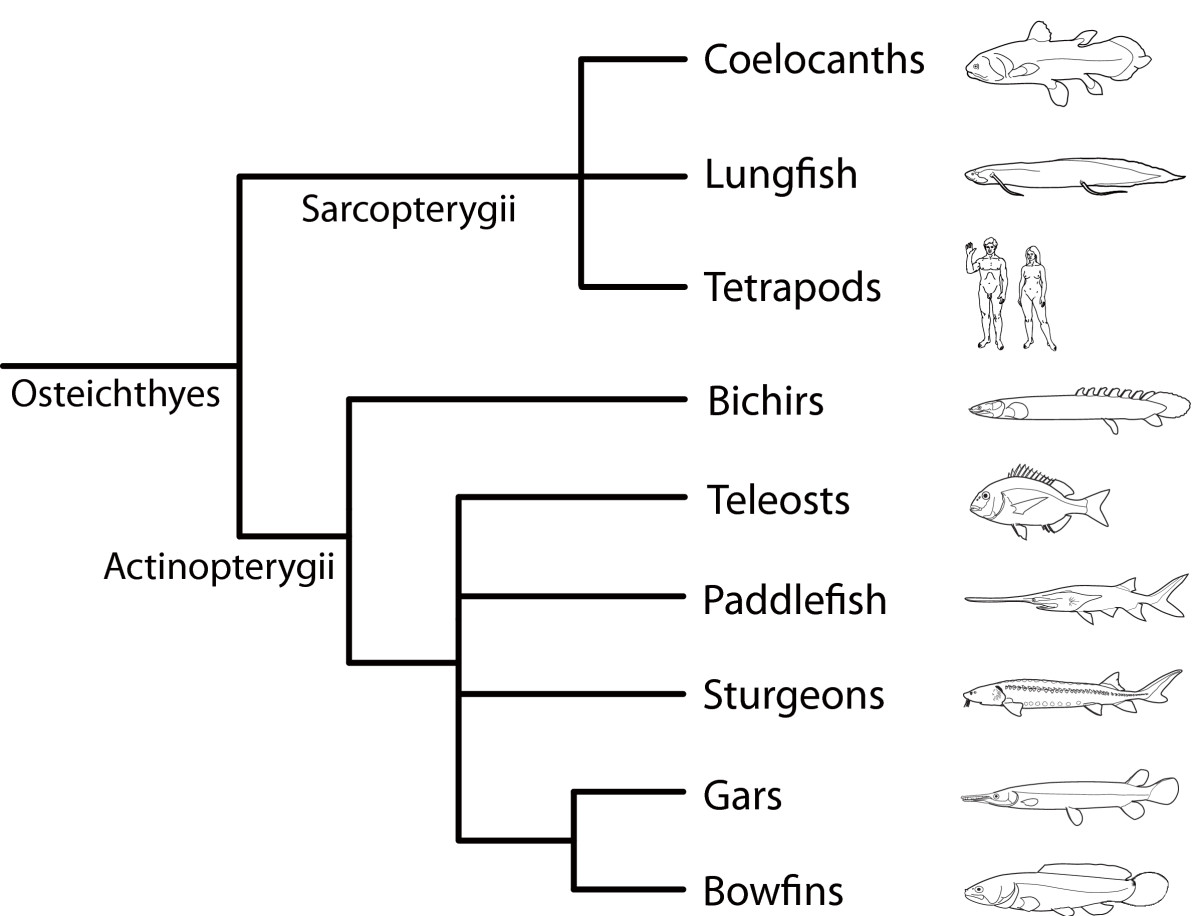

Polypterus and ropefish are perhaps the most popular ancient fish in the hobby due to their prehistoric looks, ease of care and relatively calm demeanour. Combine this with the fact that they come in various sizes, are relatively common and start at a relatively low price point and it’s a no brainer that they make for an ideal introduction into the world of Ancient fish.

The following section will equip you with some of the knowledge you need to provide the proper care and husbandry to look after your polypterus. Or, if you don’t own any yet, help you prepare for the first of many you will end up owning. They are addictive, you have been warned.

This guide will take you through the following important topics:

- Setting up your tank

- Water chemistry

- Buying your new fish

- Prophylactic treatment

- Importance of quarantine

- Nutrition

- Common health issues

- Breeding

Setting up your tank

Tank size

Your glass or acrylic aquarium is the basis of keeping fish, but which type is best for bichirs? Well as it turns out, they are not too fussy! The only things to keep in mind are the footprint of the aquarium and the depth when talking about young bichirs which should have a lower water level for ease of access to air. Let’s break it down further.

The footprint of an aquarium determines the amount of floorspace real estate available, important for relatively bottom-dwelling bichirs, especially the more sedentary upper jaws. You still want space for your fish to move around comfortably, extra water volume never hurt anyone either. If making use of grow-out tanks then there is no hard-and-fast rule for size, just make sure to graduate the fish as they start outgrowing their tank. For the purposes of this guide, I will try and simplify it and place the bichirs into 3 different groups based on their adult size. This is a rough approximation; sizes are highly variable. Here is the list:

- A) The smaller group – The fish that will max out at 12-15” - mostly upper jaw species such as P. senegalus, P. Delhezi etc

- B) The medium group – Those fish that max out at 14-20" such as wild-caught upper jaw species, P. ornatipinnis or some P. endlicheri

- C) The big boys – The larger lower jaw species that grow 20” or more

Now that we have divided the species into groups, we can have a closer look at what they require in terms of space as adults. Group A, the smaller group, should be housed in a tank with a minimum footprint of 36"x 18" (90x45cm), or even better 48x18" (120x45cm) for heavily active species such as the Senegal bichirs, it is best to adhere to a standard of 48 x 18". A standard 75 gallon would be perfect for this group.

When looking at the larger fishes in group B, the endli’s, ornates and wild-caught upper jaws a 75 gallon will not cut it for life. Depending on their size, an 18” wide tank may work for a few years, making a standard 125 gallon (72” x 18” x 23”) a good fit. For proper long term care a long, wide tank would be ideal – 72” x 24” is a good baseline for long term care. A Standard 180-gallon tank (72”x 24” x 24”) would be perfect.

Lastly, for the largest of bichirs placed in group C, you will need an equally large tank! A standard 180 would work for some time but many species can outgrow that width and as a result, these bichirs need monster tanks. The general standard is that a tank of 8’ x 3’ (96” x 36”) footprint is ideal for long term care of these hulking fish.

Filters

The filtration system is the backbone of an established tank; it is the machine that processes toxic ammonia and thereby keeps your fish alive. A good filter is vital for the long-term health of your aquarium. With so many models and varieties available, what works for polypterus? Let’s look at the requirements:

- High media capacity – Polypterus are somewhat messy eaters and consume large amounts of food, large quantities of biological media for beneficial bacteria are needed to process the resulting ammonia produced by the fish.

- Moderate turnover rate – A filter flow rate of 5-7 times your tanks volume per hour is a generally agreed-upon ideal for optimal movement of water through your filter for effective filtration. It’s also a sweet spot for not creating too much flow, polypterus live in relatively still waters in the wild.

- Escape proof – Any parts of the filter attached to the tank must be escape-proof, I have had polypterus swim up a hang on back overflow and hop out while the filter's lid was off. This is not a lesson you want to learn the hard way. Keep it sealed, any long term bichir keeper would advise this. Cover your sump intakes or pipe outlets in your lids.

Knowing this, large hang on back filters (such as an Aquaclear 110) or canister filters work well for most keepers, they provide enough flow and hold large volumes of filtration media. For monster tanks where several hang-on-backs or canisters are not affordable or efficient, a sump is the best option to provide extra water volume and hold significantly more filter media than the other filters. Do not forget to filter or cover your intakes, bichirs like exploring.

Heaters

Warm water puts the tropical into tropical aquariums, heaters are used to achieve this. The wattage that your heater requires will vary based on your climate but 2-3 watts per gallon is a good baseline.

It will be important to position your heater upright so that your polypterus can not lie on it, or make a heater guard. This is important to prevent heater burn. Heater guards are easy to make with PVC pipe, drill large holes in a length of piping and slide that over your heater. If your tank is kitted with a sump then it’s best to place your heater in there.

Substrate

In some ways bichirs act a little like a chameleon or cuttlefish; they will adapt their colouration based on their moods or to fit their environment. Therefore, the substrate you choose will influence the colouration of your fish. Dark substrates tend to bring out deeper shades of pigment and sometimes more dark barring, lightly coloured substrates tend to wash the colours out a little. The same fish can look wildly different on different substrates!

Another thing to consider is ingestion of substrate; bichirs will often swallow bits of the substrate with their food, being messy bottom-feeding fish with a big mouth and all, so it is imperative to pick a substrate that's small in grain size. Small grains of sand will find their way through the digestive system easily while gravel may remain stuck, therefore I would always use fine sand if possible. Just make sure to wash out super fine particles that may get stirred up by the fish as these are harmful to filter impellers.

Some tried and tested substrates for bichirs include:

- Black diamond blasting sand

- Pool filter sand (Silica sand)

- Garnet sands (Red, purple and brown are popular)

- River sand

- Tahiti moon sand

There are many other types of substrate available that are not mentioned here that are suitable to use, just refer to the above guidelines!

A bare bottom tank will work too. I used a bare bottom with the bottom painted black as a grow-out/quarantine tank previously. It’s a good way to keep the fish more comfortable while making the tank easy to clean.

Lighting

Less can be more, as is the case with bichirs. Low lighting is the ideal for these fish, old literature states an ideal range of 1-1.5 watts of fluorescent light per gallon of water, but many factors will influence the ideal lighting strength. Most standard lighting solutions will work well for bichirs, just avoid extremely bright or strong lights such as those designed for high-tech planted tanks. Lighting that replicates moonshine is also an option for watching more nocturnal species.

Décor

Apart from equipment and substrate, what else can you add to a bichir tank? Quite a lot. As mentioned elsewhere in the article, polypterus do enjoy having structure and places to hide. The addition of wood, plants and rocks is ideal for a bichir tank, just ensure that any sharp points are filed down to avoid injury if a bichir gets startled and swims into the décor.

Epiphytic plants (Anubias, java fern, moss), tall rooted plants (Echnidorus, cryptocoryne and Vallisneria) and floating plants often make good additions that can survive boisterous activity of bichirs. Floating plants such as water sprite are important for younger fish who like to perch among the roots. Many other species of plant will work, there are far too many to list in one place.

For some examples of other keepers aquaria, you can visit THIS THREAD LINKED

Tankmates

Listing all the potential tankmates for bichirs would be impossible, many fish will work. There are only a few considerations to consider:

- Tankmates must be large enough not to be eaten (Bichirs are predators after all)

- Overly aggressive fish must be avoided, bichirs rarely fight back with anything that won’t fit in their mouths

- Slime sucking fish – There have been instances of fish such as plecos sucking the slime coat off of bichirs, keep an eye out for this behaviour.

If it won't eat the bichir, bother the bichir or get eaten by the bichir then the fish is fair game for a tank mate.

Escape proofing

Adventure is written in the DNA of bichirs, pretty much everyone who keeps them for extended periods knows that they will often take any chance to escape, even if their excursion can be fatal. It is in the best interest of your fish to make an aquarium version of Alcatraz to avoid any mishaps and seal off any escape routes. Some recommendations to do this are listed below:

- Always use a well-fitting lid or close off the aquarium top with glass, egg crate or anything the fish can’t fit through. It is also advised to weigh this lid down if dealing with larger fish.

- Seal off any places where pipes or cables leave the tank, the fish may slip out of any holes dedicated to equipment.

- Protect your sump overflows with a strainer to bar the fish from taking a trip down to sump town.

- Lastly, close any other gaps in the tank, eg keeping the lids on HOB filter lids (Learnt the hard way personally) and so on. You don’t want any gaps.

If a bichir does manage to jump ship, don’t panic! They have an almost unrivalled air-breathing ability so will last longer out of the water than many fish, at least a few hours. Scoop up your fish and place them in a net, sometimes the slime coat is just dried out and they will begin to move again in a few hours. If the fish has been out of water for too long then, unfortunately, there is not much that can be done, it is always worth seeing if the fish recovers though.

Water chemistry

Water chemistry is one of the founding pillars of keeping fish and is an important factor when stocking your tank. Luckily for bichirs that isn’t something you need to worry about; polypterus are quite flexible.

In their natural environments in Upper and Central Africa, bichirs occupy a wide range of slow-moving rivers, swamps and lakes. The ranges of vary quite a bit, take pH. They are found in waters with a pH between 6.4 and 9.0, although this may be at the very borders of rivers feeding into Lake Tanganyika. They don’t often venture into the lake itself, rather inhabiting the swamps leading into the lake.

For aquaria you can aim for conditions in these ranges:

- pH: 6.0-8.0

- Water hardness: 2dH – 20dH (36-356 ppm or 20-200mg/l

- Temperature: 24-28°C / 75-84°F

- Nitrates < 20 ppm

- Ammonia and nitrites: 0

Polypterus are quite adaptable so most tap water sources will work. It is also important to do regular water changes to reduce nitrate (NO3) levels in the aquarium. While not immediately harmful, nitrates are known to contribute to weaker immune systems and the occurrence of opportunistic health issues. Long term exposure to high levels of nitrate could significantly reduce the lifespan of your fish. As with any other fish, it is imperative to keep Ammonia (NH3/NH4+) and Nitrite (NO2-) levels at 0, elevated levels of these metabolites can quickly become dangerous for fish.

Buying your new fish

When looking to buy a bichir at a shop it is a good idea to try and look for a healthy fish to take home to reduce the risk of death during the adjustment period. The most important things to look out for are:

- Eyes are clear

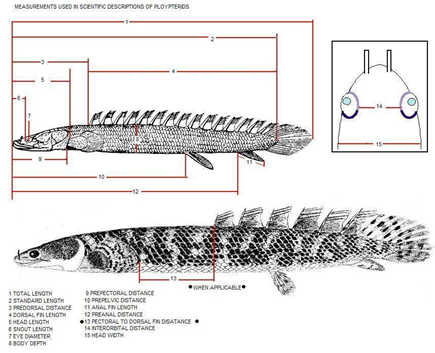

- All fins are present (Pectoral, pelvic, anal and dorsal finlets)

- No visible fungus or parasites on the fish

- Fish is active and not lethargic

- No visible deformities of the nostrils or jaws

- It should be eating in the shop, polypterus rarely avoid eating after the first day or two.

If the fish is wild-caught it may be worth placing the fish on hold for a week or two, the trapping techniques are stressful and unfortunately, some will not survive the first week or two of captivity. If they are going strong after that period, then the fish will be fine. Picking a healthy fish is important to improve the chances of successful acclimation.

Prophylactic treatment

Treating your fish for common issues is an important preventative step to prevent disease transmission between your new fish and established tankmates. It is vital to do for wild-caught fish as many, if not all, carry parasites that will be significantly more harmful in an aquarium. There are two main prophylactic treatments for bichirs that should be used:

Salt bath

This is the first step in treating new arrivals and targets external parasites. For the salt solution mix 5 teaspoons (20ml) of regular salt (NaCl) per gallon of water, or 5ml of salt per litre of water. Mix this into the transfer bucket and keep the fish in this solution for 20-30 minutes. Keep a close eye on the fish, if it becomes erratic, unresponsive or shows any other signs of acute stress then immediately move the fish into the quarantine tank and allow it to recover. This should cause most of the external parasites to drop from the fish, don’t forget to sterilize it afterwards.

It is important to use plain salt for this, products such as “Marine” salt will rapidly change the pH of the water which can contribute greatly to osmotic stress.

Chemical treatment

Once your fish is in the quarantine it is imperative to clear out any encysted or internal parasites that may remain in your bichir. Medications that target parasites, usually anti-helminthic (anti-nematode) are suited for the task, praziquantel is a key ingredient to treat a wide range of parasites. Products such as “Parasite guard” or “Parasite clear” by Jungle labs are some examples. Follow the recommended dosing regimen closely. This will clear your fish of any other parasites and protect your other bichirs outside of quarantine.

Importance of quarantine

Quarantine: a state, period, or place of isolation in which people or animals that have arrived from elsewhere or been exposed to infectious or contagious disease are placed. This process is vital for bringing new bichirs (especially wild species) into our tanks and is best done with a dedicated quarantine tank. If done properly it will save your collection from potential parasites or diseases as well as reducing the amounts of medication you may need.

The setup of a quarantine tank can be as simple as an aquarium with a filter, heater, plastic plants, and structure for the fish to hide in. It can be more complex, but everything should be simple to take apart and sterilize after the quarantine period. This same tank can be used as a hospital tank if needed.

The actual process of quarantining fish is easy: Set up the tank, acclimate the fish then observe it for a period. This lets you keep an eye out and treat any potential issues or diseases, perform prophylactic treatment, and can ensure that the fish is eating readily before addition to the main tank. A time span of two weeks should be the minimum considered, with 4-6 weeks being ideal as an observation period. If no problems are apparent, it is then safe to add the fish to your main tank.

Nutrition

Feeding bichirs is simple enough, they are adept at tracking food down and eat heartily, but what do you feed them? There are 3 main categories of food options you can give your fish: Pelletized, frozen and live foods. The types, benefits and caveats of each type will be discussed individually in the following paragraphs.

To summarize this at the beginning, it is important not to overfeed your bichirs due to their ability to pack on food. In a captive environment, they do not exert as much energy as a wild fish would, therefore making them susceptible to obesity and fatty liver disease, a common cause of death for many captive fish. It is best to feed them till they are visibly full; you get a feel for how much food they eat and can adjust according to the fishes’ size.

The best diet is a mixed diet, this is key for balanced nutrition.

Pelletized foods

A backbone of home aquaria, pellet foods are the simplest way to deliver quality nutrition to your pets. There is a bewildering array of pellet types aimed at different groups of fish made with different ingredients, there is nothing made specifically for bichirs though. Bichirs will often eat sticks or pellets such as shrimp, fish, seafood, worm, spirulina, brine shrimp or algae-based foods. Even cichlid pellets work.

To choose your foods it is best to look for the following in the nutritional information and ingredients:

- The first 3 ingredients are animal or algae-based before moving to filler ingredients, eg Fish meal, shrimp meal and krill, “fillers and other ingredients”. These foods are more nutritious.

- Protein content: 40-45%+ is ideal for carnivorous fish

- Fat: 3-6% maximum

- Fibre: 2-4% maximum

A good pellet should form the majority of your bichirs diet and can be supplemented with frozen or live foods.

Frozen foods

Aptly named for foods that are stored in your freezer, frozen foods make for a good supplement to a bichir diet. These products will often be available at your local fish shop or seafood section of a supermarket. The list includes:

- Bloodworms

- Krill

- Brine shrimp

- Mosquito larvae

- Tubifex worms

- Squid

- Silversides

- Other non-oily fish fillets

- De-shelled market shrimp

These can be thawed and fed to your fish. For raw seafood, particularly thiaminase-containing foods such as market shrimp, should be pre-soaked in a vitamin product that contains vitamin B1 to combat deficiency caused by thiaminase. It doesn’t hurt to add vitamins to raw seafood in general. For a better list of seafoods containing thiaminase

click here

Live foods

The final, and smallest, component of your bichirs diet can be live foods. This includes:

- Small shrimp

- Insects such as small freshly moulted cockroaches or mealworms

- Crickets

- Earthworms

- Small fish

- Insect larvae

- Even frogs

These should only be given as occasional treats. Chitinous insects such as mealworms and cockroaches should only be fed after moulting as their otherwise hard exoskeleton can cause intestinal blockages.

Any feeder fish should ideally be bred at home or quarantined for extended periods due to the sub-standard conditions in which they are raised, and the high rates of disease and parasites. Goldfish should be avoided as they are oily, contain lots of thiaminase and are not nutritious compared to pellets or prepared frozen foods.

My fish isn’t eating! Help!

Despite their notoriously voracious appetite, it is not uncommon for bichirs to ignore food after acclimation or in response to changes in their environment, refuse prepared foods and sometimes they just avoid food for no apparent reason. Firstly, do not panic; bichirs can go long periods without food and will very rarely starve to death voluntarily. Secondly, there are a few things that can be done to get them eating again or get them eating what you want them to.

For newly added fish it is normal for them to refuse to eat while they are settling in; capture, transport and acclimation is a stressful process and as a result, they will not eat. Be patient, the fish will eventually give in. This can take anywhere from days to weeks but once they are settled, they will eat well.

Another commonly encountered issue is for a bichir to ignore pellets, especially from wild-caught fish or those used to eating live feeders. Non-moving foods may not appeal to them and are ignored. To rectify this the fish can be weaned off live food with frozen foods such as silversides, shrimp, or krill. Once they are eating dead foods readily then pellets can be added at feeding time, eventually, the fish should start eating some pellets and will begin to accept dry foods.

Eating strikes are a common response to stresses, sickness or will happen at random. If your tank is well maintained and any health issues are treated, then your bichirs will begin to eat again soon after. Strikes are not something to worry about and will rectify on their own in time.

Common health issues

Bichirs are susceptible to many of the same ailments as other fish but also have a few ailments that are more unique to their genus or are generally more susceptible to. For a more thorough article on health issues and answers then please

click here

Bloat

The most common cause of bloat is a condition named “Dropsy”. This is characteristically a side effect of a decline in osmotic regulation with the kidneys, causing the fishes body cavity to swell with fluid. If caught early this can be treated with Metronidazole, the treatment regimen is detailed in the thread linked above. Common causes are poor nutrition and/or low water quality that allows opportunistic infections to reduce kidney function. The addition of a Calcium chloride-based salt (such as rift lake salt) in trace amounts is said to help maintain homeostasis in bichirs.

If your fish has a bloated stomach specifically it is often an indication of overfeeding or a build-up of gas, sometimes resulting in a floating fish. This will eventually find its way out. Offering algae or spirulina-based foods occasionally will help reduce the likelihood of this as plant proteins are important for gut health.

If bloat persists longer than a day, then it would be advised to start treatment for dropsy.

Internal worms

Flatworms, spiny headed worms, and tapeworms are often found in wild-caught fish. Most of these require an intermediate host (eg crustaceans) that are eaten to transmit the worms. If the fish is starving, the worms will be expelled. Praziquantel can be used to treat suspected worms, it is also standardly dosed in quarantine for this reason.

Bichir worms

Macogyrodactylus is a genus of flukes that will commonly be present on wild-caught bichirs. They resemble small white threads on the body of the fish. They spread easily, but only to other bichirs. Praziquantel is a tried and tested treatment for bichir worms.

Anchor worms

Another type of “worm”, these crustaceans (Lernaea haplocephala) attach themselves to the bodies of bichirs and again are mostly found on wild-caught fish and will spread to other bichirs. As with bichir worms they are treated with a round of praziquantel and it is best to do so in quarantine.

Fin damage

Split or damaged fins occur because of aggression from other fish, leaving them tattered. In most cases, this will heal given time and clean water. In rare cases fins can be split permanently, such is the case with this P. lapradei owned by

Ledzepp6266

Ledzepp6266

It is unclear whether this was caused by a birth defect or deep damage before he was acquired by the current owner. This sort of injury or defect is rare but not unheard of.

If your bichir has damaged fins they will often recover without any permanent changes.

Breeding

Despite their widespread occupation in aquaria around the globe, breeding of polypterus at home is still relatively uncommon. Certain species such as senegals, delhezi, lapradei, endlicheri and some others are bred in commercial farms for the trade, most likely through artificial insemination, but their secrets are closely guarded.

In a hobby setting, it is rare for bichirs to breed, likely due to the extremely long maturation time of female fish. When bichirs are of breeding age they will reproduce frequently with eggs often turning up in filters or sumps.

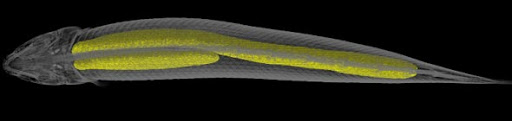

To breed bichirs at home it is best to use a breeding mop, the fish lay eggs in between plants in nature so a green woollen mop will do the trick. Fish ready to spawn will display courtship behaviour for at least a day (read under behaviour) and will proceed to mate and release their eggs into the mop. The eggs can be removed and added to incubation containers. By most accounts they hatch within 3-4 days, living from their yolk sac for another week. Once the yolk sac is consumed they can be fed with freshly hatched brine shrimp (Artemia nauplii) or microworms. Regular breeder

giseok jung

giseok jung

uses tubifex worms to raise them further.

Conclusion

Bichirs are truly amazing fish, if this article hasn’t convinced you of that then I don’t know what more could be cooler than a living relic, a window into the past. I have learnt a lot of new things writing this article and I trust it will be enriching to everyone who takes the time to go through it. Thanks for reading!