I don't get it.

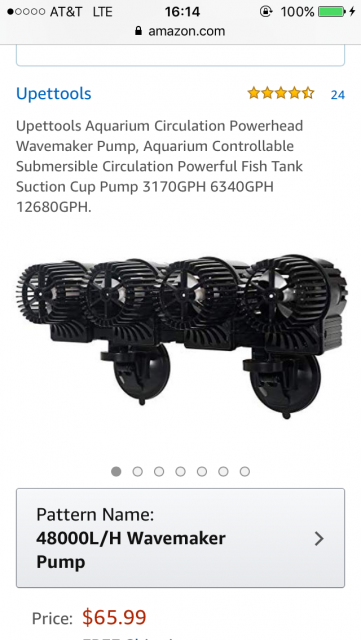

Why are 2,500 GPH+ powerheads so expensive? The ones that really get the gravel moving, and grind feeder fish into food coloring so fast they might actually qualify as an ethically legal method of dispatching fish: If you work in a research lab, you usually slow their metabolism down through temperature, and then toss them in a garbage disposal to sever the cranial nerve. SAme thing. Anyways....

I'd expect to pay no more than $500 for a workhorse commercial grade powerhead that moves 2,500 GPH for years. (Warranty should be AT LEAST one year). Tunze and Ecotech tip that price line, and there are a few Custom/boutique powerhead makers out there, some in Japan and DE, charging 1K, 2K, $3K. And I question whether the total cost / COGS to the manufacturer is even close to that amount, $750 on up.

There's been discussion around this topic before but I have yet to see a breakdown of why and what makes the higher end, high flow powerheads an appropriate value equation for the customer. (E.g., people pay for it now, and pay what they pay, but will that change?)

My thoughts:

A powerhead is a motor. AC, or DC. Generally, AC is more efficient, DC is easier/less expensive to control.

Instead of thinking about what a good powerhead is, I'd like to think about the reasons any powerhead fails: What engineering problems do makers of powerheads face? Considering a powerhead is a motor and fluid waveguide or turbine? And in the face of the inevitability of those problems, in what way does a powerhead fail most often? - catastrophically? Or in a way which is unsafe (electrocution? join the club) or requires complete replacement.

Common Causes of Powerhead Failure

(please add more or correct! I am not an engineer)

- Frictional wear. Over time, a motor or what work/propeller/shaft a motor drives, will fail due to friction. Always. All mechanisms fail due to friction eventually (there's even a degree you can get in this, called 'Tribology') This friction may be intrinsic to the mechanism of the motor - maybe there is intentional drag or some sort of braking. This friction may be due to small or large particles forming within the motor housing, or being introduced from outside particles.

- Rotational Eccentricity (OK, while perhaps all failure might be caused by some sort of friction, there are subcategories...) Commonly, rotational eccentricities in the alignment of the centricity of the spindle will be suboptimal, or fall out of true over time - as the spindle begins to spin eccentrically, or wobble, the shaft and bearings experience more stress in one location and less in others, causing nasty feedback, and eventually tearing itself or its housing apart.

- Fluid Dynamic/Mechanical Design: Please excuse my abuse of terminology. Component stress and failure from poor or out-of-context design of fluid dynamic(al) channels or parts. For example, if a powerhead of 20W pulls 4,000 GPH through a globe-like strainer, that strainer (which is also the intake) should have fins and an overall shape which is optimized for the amount of water per second passing through the blades in the directions they are pulled toward negative pressure. If the enclosure is not well designed, the powerhead may fail for at least two reasons. 1) The fins/ribs on the enclosure may crack or the entire assembly implode - too much juice in the juicer. 2) The shape of the enclosure causes uneven or excessive force exerted on areas of the path of the blades, which cause the blades to snap or dislodge, or, the motor runs at reduced efficiency and burns out.

- Electrical failure: can be thermal, or, especially in marine environments, an electrical pathway can easily corrode or short out to another pathway inside the motor housing - causing either motor failure or dangerous electrical current to leak into the tank

- Backflow and Countercurrent Failure: Many powerheads will work just fine if they are the only one in a large tank, but as soon as additional powerheads are introduced forcing water at the blades and intake in wacky directions, or, the back of the powerhead is up against the glass, or, the flowrate is too large for the tank size, complicated currents and eddies form - which are sometimes desirable - but if the shape and motion of the powerhead is not well designed, it may not be able to accommodate these opposing flows on a 24/7/365 duty cycle.

- Material Failure. When the materials the powerhead are made from - the aluminum shaft/spindle, the plastic housing - crack, break, cleave, etc. If these materials fail in less than a year, my guess is this is more often caused by repetitive stresses which could have been avoided or, curve ball, degradation of plastics in the presence of strong ultraviolet light, which all reef aquariums have. Choosing a polymer more resistant to UV might only be cents or dollars more than what we usually see. (Although machining from aluminum or Stainless would be, er, much more expensive)

- Control/CPU failure: This is a tricky one. Which I'd rather not delve in to, because I'd like to focus only on the water moving mechanism itself without controls, although there's really no way to NOT discuss controllers since they are so ubiquitous. Controllers put unique demands on powerheads, and it may be difficult to separate whether it is the powerhead which failed, or the controller.

Reasons Why the Above Failures Are NOT HARD aka Inexpensive to Solve or Optimize:

(Basically, reasons why powerheads over $500 are probably overpriced)

- Small Electrical motors are simple and inexpensive. Or, they should be for the aquarium application. Someone might point out that turbines in the Hoover Dam are EM motors, so are the drivetrains of a hybrid high-end vehicle. True. But for the aquarium, we aren't actually moving that much water, at high pressures or flowrates, compared to a hydroelectric turbine or (electric?) boat motor, for example. Powerheads don't need to worry about heavy, destructive cavitation. I believe the difficulty of designing an underwater propeller is compounded when fluid velocities approach or exceed the speed of sound in water, which is about 1,500 meters/second. I doubt that any area of a powerhead experiences that type of velocity, except for the tips of the blades, and near the cone and bladeroot. Further, they are only discharging electricity in a mechanical way in one direction, vs. needing to both accept (charge) a battery and use a battery or current as a drive source. They do one thing. They are about the most primitive and elementary electrical component/assembly there is, even if the windings look fancy. The technology is ancient. Commercially, they became viable in about 1880. That's 140 years - and the simple ones, like those in powerheads, haven't changed much.

- Optimizing flow to load and enclosure should be easy, because it's done by software, and it has been done before. Efficient rotor and turbine design goes back to at least the 18th century, and if you want to get picky about it probably a thousand years or so. Practically, the basic equations describing the mechanics of the movement of fluids might be 200 years old, with the more advanced and reliable ones being the same 150 odd years old. This stuff has already been figured out. And what's been figured out doesn't have to be done by hand anymore. Computer simulation and modelling allows engineers to effectively build and test the motor and fluidics before any prototypes have been made, without doing any heavy math. You just type in what you want, and tweak for a few weeks/months, and the computer spits out something good enough.

- Powerheads operate underwater - because they operate underwater in a denser and very special fluid (H20), there is less friction, and there is little to no need for thermal management to prevent the motor from catching on fire or burning out because as long as the motor is working, it's pulling cooler water over itself and cooling itself down much more efficiently than if it were operating in air.

The costs to design and manufacture a powerhead might be, for a run of 10,000 units over a 2-3 year production and sales cycle:

- $150k-400k for Industrial engineering or design

- $50K to make a mold for injection molding or casting

- $10K in raw materials: PVC, L/HDPE, PET, etc

- $30k for safety and FCC, UL certificates

- $150K for manufacturing labor

- $10K for simple quality control like burnin and visual inspections

- $15K marketing

- $10k PR

- Maybe $5K max for the software development of controllers. You really aren't doing that much except controlling amplitude, and in some cases directionality or diffusion of flow, and many controllers attempt to replicate random patterns. DC is as simple as a digital potentiometer I'd think, and A/C or DC could also use a $1-3 component called a PWM to control amplitude. Also, software can be copy and pasted, which real things cannot.

- $90 MAX maximum for a top quality 2-20W brushless sealed or brushed DC or AC motor with super long MTTF, purchase of 10,000 bumps price down from a retail of $150 or so.

- $10 per in other parts and raw materials

- $10 for neodynium magnets

- $20 per for electrical components

- $25 for enclosure and attachment

- $3 per unit for palette distribution to warehouse or wholesaler

- What am I forgetting?

For a 5,000 GPH model, I would expect an absolute top tier threshold with controller to cap out at $750. The Cadillacs, and a few Rolls, but not the ferraris. Why are the ferraris worth what they are?

This is not - necessarily - a question on whether expensive powerheads are worth it, rephrased, that the purchase is a fair and valuable price, or... no wait, actually that may be the question!

Why are 2,500 GPH+ powerheads so expensive? The ones that really get the gravel moving, and grind feeder fish into food coloring so fast they might actually qualify as an ethically legal method of dispatching fish: If you work in a research lab, you usually slow their metabolism down through temperature, and then toss them in a garbage disposal to sever the cranial nerve. SAme thing. Anyways....

I'd expect to pay no more than $500 for a workhorse commercial grade powerhead that moves 2,500 GPH for years. (Warranty should be AT LEAST one year). Tunze and Ecotech tip that price line, and there are a few Custom/boutique powerhead makers out there, some in Japan and DE, charging 1K, 2K, $3K. And I question whether the total cost / COGS to the manufacturer is even close to that amount, $750 on up.

There's been discussion around this topic before but I have yet to see a breakdown of why and what makes the higher end, high flow powerheads an appropriate value equation for the customer. (E.g., people pay for it now, and pay what they pay, but will that change?)

My thoughts:

A powerhead is a motor. AC, or DC. Generally, AC is more efficient, DC is easier/less expensive to control.

Instead of thinking about what a good powerhead is, I'd like to think about the reasons any powerhead fails: What engineering problems do makers of powerheads face? Considering a powerhead is a motor and fluid waveguide or turbine? And in the face of the inevitability of those problems, in what way does a powerhead fail most often? - catastrophically? Or in a way which is unsafe (electrocution? join the club) or requires complete replacement.

Common Causes of Powerhead Failure

(please add more or correct! I am not an engineer)

- Frictional wear. Over time, a motor or what work/propeller/shaft a motor drives, will fail due to friction. Always. All mechanisms fail due to friction eventually (there's even a degree you can get in this, called 'Tribology') This friction may be intrinsic to the mechanism of the motor - maybe there is intentional drag or some sort of braking. This friction may be due to small or large particles forming within the motor housing, or being introduced from outside particles.

- Rotational Eccentricity (OK, while perhaps all failure might be caused by some sort of friction, there are subcategories...) Commonly, rotational eccentricities in the alignment of the centricity of the spindle will be suboptimal, or fall out of true over time - as the spindle begins to spin eccentrically, or wobble, the shaft and bearings experience more stress in one location and less in others, causing nasty feedback, and eventually tearing itself or its housing apart.

- Fluid Dynamic/Mechanical Design: Please excuse my abuse of terminology. Component stress and failure from poor or out-of-context design of fluid dynamic(al) channels or parts. For example, if a powerhead of 20W pulls 4,000 GPH through a globe-like strainer, that strainer (which is also the intake) should have fins and an overall shape which is optimized for the amount of water per second passing through the blades in the directions they are pulled toward negative pressure. If the enclosure is not well designed, the powerhead may fail for at least two reasons. 1) The fins/ribs on the enclosure may crack or the entire assembly implode - too much juice in the juicer. 2) The shape of the enclosure causes uneven or excessive force exerted on areas of the path of the blades, which cause the blades to snap or dislodge, or, the motor runs at reduced efficiency and burns out.

- Electrical failure: can be thermal, or, especially in marine environments, an electrical pathway can easily corrode or short out to another pathway inside the motor housing - causing either motor failure or dangerous electrical current to leak into the tank

- Backflow and Countercurrent Failure: Many powerheads will work just fine if they are the only one in a large tank, but as soon as additional powerheads are introduced forcing water at the blades and intake in wacky directions, or, the back of the powerhead is up against the glass, or, the flowrate is too large for the tank size, complicated currents and eddies form - which are sometimes desirable - but if the shape and motion of the powerhead is not well designed, it may not be able to accommodate these opposing flows on a 24/7/365 duty cycle.

- Material Failure. When the materials the powerhead are made from - the aluminum shaft/spindle, the plastic housing - crack, break, cleave, etc. If these materials fail in less than a year, my guess is this is more often caused by repetitive stresses which could have been avoided or, curve ball, degradation of plastics in the presence of strong ultraviolet light, which all reef aquariums have. Choosing a polymer more resistant to UV might only be cents or dollars more than what we usually see. (Although machining from aluminum or Stainless would be, er, much more expensive)

- Control/CPU failure: This is a tricky one. Which I'd rather not delve in to, because I'd like to focus only on the water moving mechanism itself without controls, although there's really no way to NOT discuss controllers since they are so ubiquitous. Controllers put unique demands on powerheads, and it may be difficult to separate whether it is the powerhead which failed, or the controller.

Reasons Why the Above Failures Are NOT HARD aka Inexpensive to Solve or Optimize:

(Basically, reasons why powerheads over $500 are probably overpriced)

- Small Electrical motors are simple and inexpensive. Or, they should be for the aquarium application. Someone might point out that turbines in the Hoover Dam are EM motors, so are the drivetrains of a hybrid high-end vehicle. True. But for the aquarium, we aren't actually moving that much water, at high pressures or flowrates, compared to a hydroelectric turbine or (electric?) boat motor, for example. Powerheads don't need to worry about heavy, destructive cavitation. I believe the difficulty of designing an underwater propeller is compounded when fluid velocities approach or exceed the speed of sound in water, which is about 1,500 meters/second. I doubt that any area of a powerhead experiences that type of velocity, except for the tips of the blades, and near the cone and bladeroot. Further, they are only discharging electricity in a mechanical way in one direction, vs. needing to both accept (charge) a battery and use a battery or current as a drive source. They do one thing. They are about the most primitive and elementary electrical component/assembly there is, even if the windings look fancy. The technology is ancient. Commercially, they became viable in about 1880. That's 140 years - and the simple ones, like those in powerheads, haven't changed much.

- Optimizing flow to load and enclosure should be easy, because it's done by software, and it has been done before. Efficient rotor and turbine design goes back to at least the 18th century, and if you want to get picky about it probably a thousand years or so. Practically, the basic equations describing the mechanics of the movement of fluids might be 200 years old, with the more advanced and reliable ones being the same 150 odd years old. This stuff has already been figured out. And what's been figured out doesn't have to be done by hand anymore. Computer simulation and modelling allows engineers to effectively build and test the motor and fluidics before any prototypes have been made, without doing any heavy math. You just type in what you want, and tweak for a few weeks/months, and the computer spits out something good enough.

- Powerheads operate underwater - because they operate underwater in a denser and very special fluid (H20), there is less friction, and there is little to no need for thermal management to prevent the motor from catching on fire or burning out because as long as the motor is working, it's pulling cooler water over itself and cooling itself down much more efficiently than if it were operating in air.

The costs to design and manufacture a powerhead might be, for a run of 10,000 units over a 2-3 year production and sales cycle:

- $150k-400k for Industrial engineering or design

- $50K to make a mold for injection molding or casting

- $10K in raw materials: PVC, L/HDPE, PET, etc

- $30k for safety and FCC, UL certificates

- $150K for manufacturing labor

- $10K for simple quality control like burnin and visual inspections

- $15K marketing

- $10k PR

- Maybe $5K max for the software development of controllers. You really aren't doing that much except controlling amplitude, and in some cases directionality or diffusion of flow, and many controllers attempt to replicate random patterns. DC is as simple as a digital potentiometer I'd think, and A/C or DC could also use a $1-3 component called a PWM to control amplitude. Also, software can be copy and pasted, which real things cannot.

- $90 MAX maximum for a top quality 2-20W brushless sealed or brushed DC or AC motor with super long MTTF, purchase of 10,000 bumps price down from a retail of $150 or so.

- $10 per in other parts and raw materials

- $10 for neodynium magnets

- $20 per for electrical components

- $25 for enclosure and attachment

- $3 per unit for palette distribution to warehouse or wholesaler

- What am I forgetting?

For a 5,000 GPH model, I would expect an absolute top tier threshold with controller to cap out at $750. The Cadillacs, and a few Rolls, but not the ferraris. Why are the ferraris worth what they are?

This is not - necessarily - a question on whether expensive powerheads are worth it, rephrased, that the purchase is a fair and valuable price, or... no wait, actually that may be the question!